Yes, Australia is currently a major fossil fuel exporter. But that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t co-host COP31 in 2026. Here’s the case for having it in this region.

Firstly, an Australia-Pacific COP31 would result in hosting being in the hands of nations that are responsible for more of the planet than any previous COP host.

Australia is the sixth-largest nation on Earth. It’s true that Brazil, the host of next year’s COP, has a larger land mass than Australia. So too does Canada, which hosted the COP in 2005.

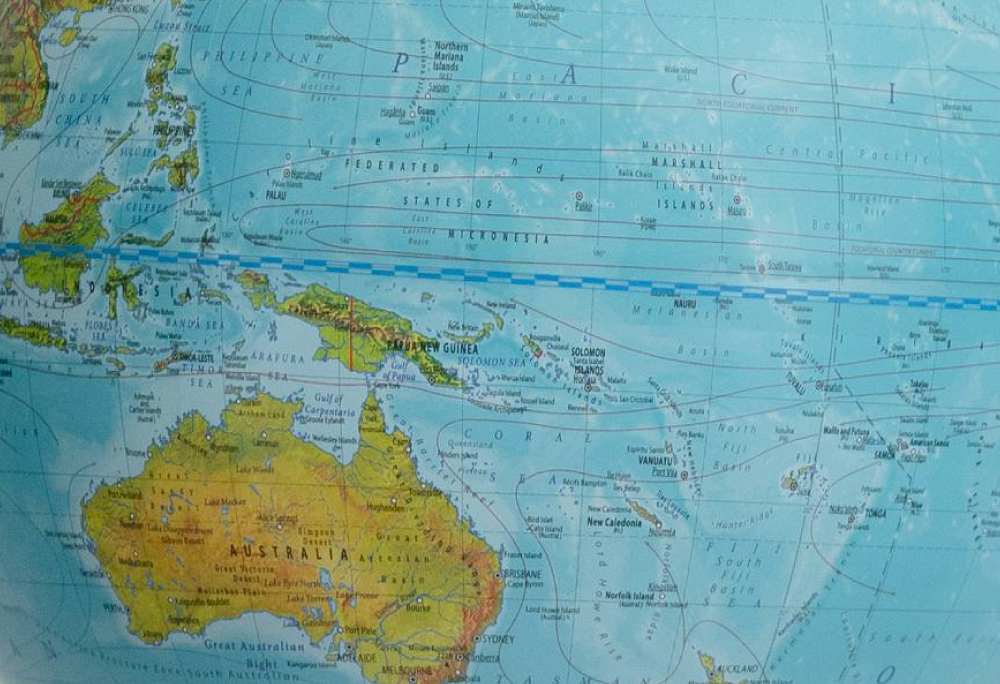

But COP31 would be held in conjunction with Pacific neighbours – and the small island states that comprise our Pacific neighbours are also large ocean states.

This would make an Australia-Pacific COP31 ‘the biggest COP’ – not in the superfluous sense of number of attendees, but in the more important sense that its hosts would jointly be custodians and stewards of a very large part of our planet.

There is an important follow-on from that. An Australia-Pacific COP would be much more likely to give agriculture, land-based ecosystems, and oceans the focus that they deserve.

Partly, this would build on the work that Brazil will do next year. Brazil is very conscious of the need to better coordinate the ‘Rio trio’ of conventions on climate change, biological diversity, and desertification that all had their genesis in the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

An Australia-Pacific COP would be well-positioned to ensure the Brazil momentum is maintained, and would also ensure oceans receive the attention they deserve.

This is important, because it is not a given that agriculture, nature, and oceans receive sufficient attention at climate COPs. For example, all three issues received limited attention at COP29.

Secondly, an Australia-Pacific COP31 would be the first COP to have co-hosts that encompass signatories to the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty proposal.

Of the 14 nations that are signatories to the treaty proposal, the vast majority are in the Pacific – including Vanuatu (which founded the initiative), Tuvalu, Tonga, Fiji, the Solomon Islands, Palau, Samoa, Nauru, the Marshall Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia.

Having hosts that comprise a major fossil fuel exporter and those seeking a formalised fossil fuel phase-out could have significant potential to deliver a good result on a fossil fuel exit strategy.

Thirdly, an Australia-Pacific COP would be almost the first COP to encompass members of the V20 grouping of 70 of the world’s most climate change-vulnerable developing countries.

Pacific members of the V20 – which has been a powerful advocate for sensible and substantial financial reforms to fight climate change – include PNG, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Nauru, and Palau.

(Fiji hosted the COP in 2017, but for logistics reasons the event took place in Bonn, Germany).

Fourthly, having an Australia-Pacific COP would also help to dispel disinformation in Australia about the need to decarbonise. Lies and misinformation about climate change and climate change solutions are much more likely to wither away when a nation or region hosts a massive event like a COP. In addition, by 2026, Australia’s progress in decarbonising will be even more visible.

Finally, if COP31 isn’t in Australia and the Pacific, then where should it be? Turkey, which is highly dependent on fossil fuel imports, mostly from Russia, is the other contender to be COP31 host. It is by no means a given that it would be a more ambitious holder of the COP31 presidency. In fact, it’s highly unlikely (unless, of course, the Coalition wins the next federal election).

Meanwhile, there are some changes that should be made to the COP process, whoever hosts it.

Firstly, it’s time for a renewed push – starting in Brazil – to make it absolutely clear that rapid action can’t be vetoed by a tiny number of countries. The UNFCCC process has – on one view – coped surprisingly well with its murky decision-making procedures.

But there is no doubt that these ill-defined procedures have empowered laggards to significantly slow action and ambition.

Secondly, although the COP can’t be everything, it can come close to being everywhere. The process needs to be opened up a lot, via a dramatic scaling of its virtual observer/participant arrangements.

The shift should entail a major rethink of the public-facing green zone. This forum has huge potential, which can best be tapped by designing the green zone much more deliberately to be a global, virtual hub.

There are also some much more banal changes that would be helpful.

It would be useful to tweak the way that side events operate in the more restricted blue zone. For a start, there needs to be one calendar that lists all side events in the side event rooms and in the various delegation pavilions.

Again, these side events need to be opened up a lot more for virtual participation – particularly as many of those physically present at these events are in FOMO mode, and spend nearly the whole time scrolling their phones.

Also, future COP presidencies need to be a lot better at hitting ‘record’. Why are so few side events actually recorded for on-demand viewing? The failure to do so means their impact is largely transitory, and a significant amount of new, important knowledge isn’t widely disseminated. This needs to change.

Finally, there is one aspect of achieving climate change action that I think needs much greater attention – climate change communication, which is barely discussed at COPs.

Climate change communication presents very different challenges in various economies. For example, climate change communication issues facing LDCs (least-developed countries) are very different to those facing MDCs (Murdoch-dominated countries). However, across the board these matters need more air-time at COPs.